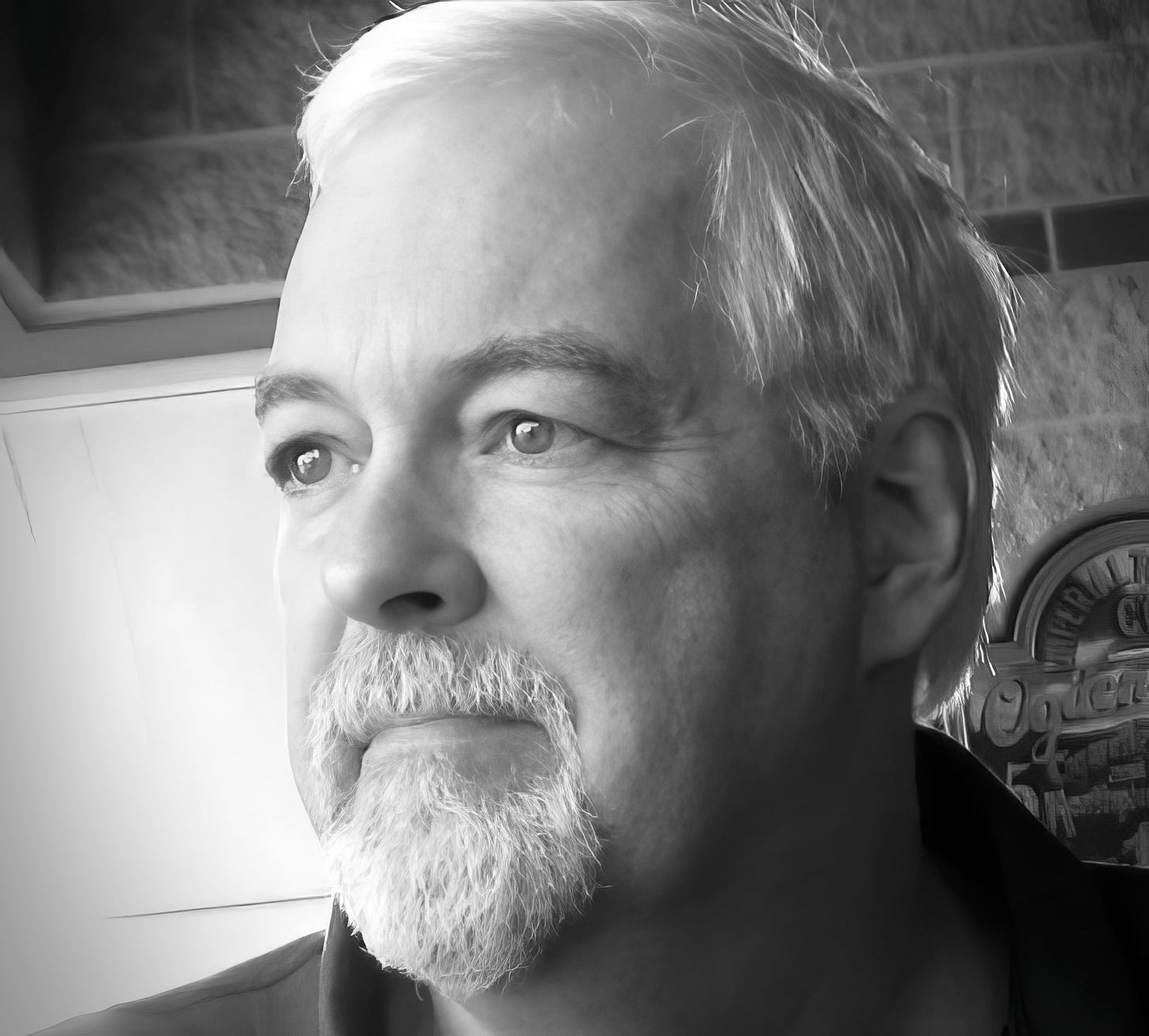

Long Story Short ★ RON RANDALL

A Creative Who Found the VALUE of CREATING COMICS on HIS TERMS

Hailing from Portland, Oregon, comic creator, RON RANDALL, has been a mainstay in comics for the last several decades. His career path has led him to work with some of the most interesting characters at the largest comic publishers. But deep down, his own creations have been the monumental achievement of his career. Join us as we talk about his background and what led to the pursuit of his comic, TREKKER.

BTP: Tell us a little bit about yourself and why you decided to pursue your career as a creative storyteller.

RANDALL: Looking back, I've come to believe that I DIDN'T "choose" to pursue my comics career. It was more like I had no choice. Once, as a grade schooler, the idea got in my head that, "people get to make comics for a living?!?" it just never left.

BTP: So, back when this realization for you happened, before industry magazines, before the internet, what was your approach from getting from that childhood moment to actually producing sequential comic art? What was one of your favorite characters you created from that era?

RANDALL: Well, I was just a grade school kid when this epiphany struck, so I had no plan or thought of how I could possibly actually become a working cartoonist. It was like saying you wanted to be an astronaut or something equally unrealistic. I just started drawing characters and making up stories for my own amusement and that of a few kindred spirit friends. It wasn’t until years later, When I was in high school, I think, when there WERE a few industry mags, that I saw an invite from Marvel to send in samples. Which I naively did. I wasn’t ready for prime time, but they did get back to me with enough encouragement to keep me going. But it wasn’t until a few years later when I saw an ad for the Kubert School in a trade mag that things started to get “real”.

As to your other question, my “creation as a kid were pale imitations of popular Marvel and DC characters: “The Mutants”, “WeatherMaster”… nothing to put any weight on.

BTP: Still, what’s great about that, is how our minds work to realize our dreams. It’s usually a happy place that has fueled us well into adulthood. Who was your first advocate or earliest mentor that helped in your pursuits?

RANDALL: I was lucky, I had a very patient and supportive mother, plus a couple of close friends who were also into comics. So, my buddies and I would get together and spend time designing our own characters and drawing (very crudely, of course) their adventures. Over time, the buddies drifted away to other interests, but I never stopped writing and drawing my own stories.

BTP: That sounds similar to my own origin story. I can’t tell you how many hours I spent arguing over whose character was stronger, hopped up on Kool-Aid and hubris. Have you ever, as a professional, revisited some of those older characters? At that time was there a comic you wanted to draw for Marvel or DC?

RANDALL: As I say, none of my “early creations” had much to recommend themselves for revisiting. They just functioned well to get me started. Exercises, you might say. And sure—I wanted to draw several characters—the FF, Flash, Superman… the books I fell in love with as a kid. Once I stumbled upon Flash Gordon, I wanted more to be like the artists—Raymond, Wood, Williamson, than to draw specific characters.

BTP: Oh…now we’re talking. You just named three of my early comics art heroes! I’d add Hal Foster in there, too. When you originally set out to study and learn, when did your learning take place and what resources did you have available to you?

RANDALL: My learning took place at a desk in my bedroom; the same one I did my homework on. There, I'd pour over the pages of the latest comics I'd bought trying, often slavishly, to copy Kirby or Windsor-Smith or whoever. That's what you do when you're young and starting. Imitation. Over time, all those influences come to gel into something that is just "YOU", but it's a process and for most of us, it takes time.

BTP: That’s funny, that is also exactly my setup from childhood. Though, it never occurred to me to imitate other artists until I was close to graduating high school. I was a huge fan of Neal Adams’ Deadman and Sienkiewicz’s Moon Knight, which was his version of Neal Adams. Were you writing and illustrating your own full-length stories even back then?

RANDALL: I was! They were rough and primitive, and very derivative being pale imitations of the comics I was reading, of course. But it got me started. And from the beginning, I was more interested in telling a story than in concentrating on one illustration. I don’t know where that impulse came from, but it was there from pretty much the start.

BTP: Like you said, you sound like you had little choice in the matter. It was just gonna happen. When compared to your early work experience do you feel like you were well-educated to step into a role or was there a larger divide between school and actual pipeline production?

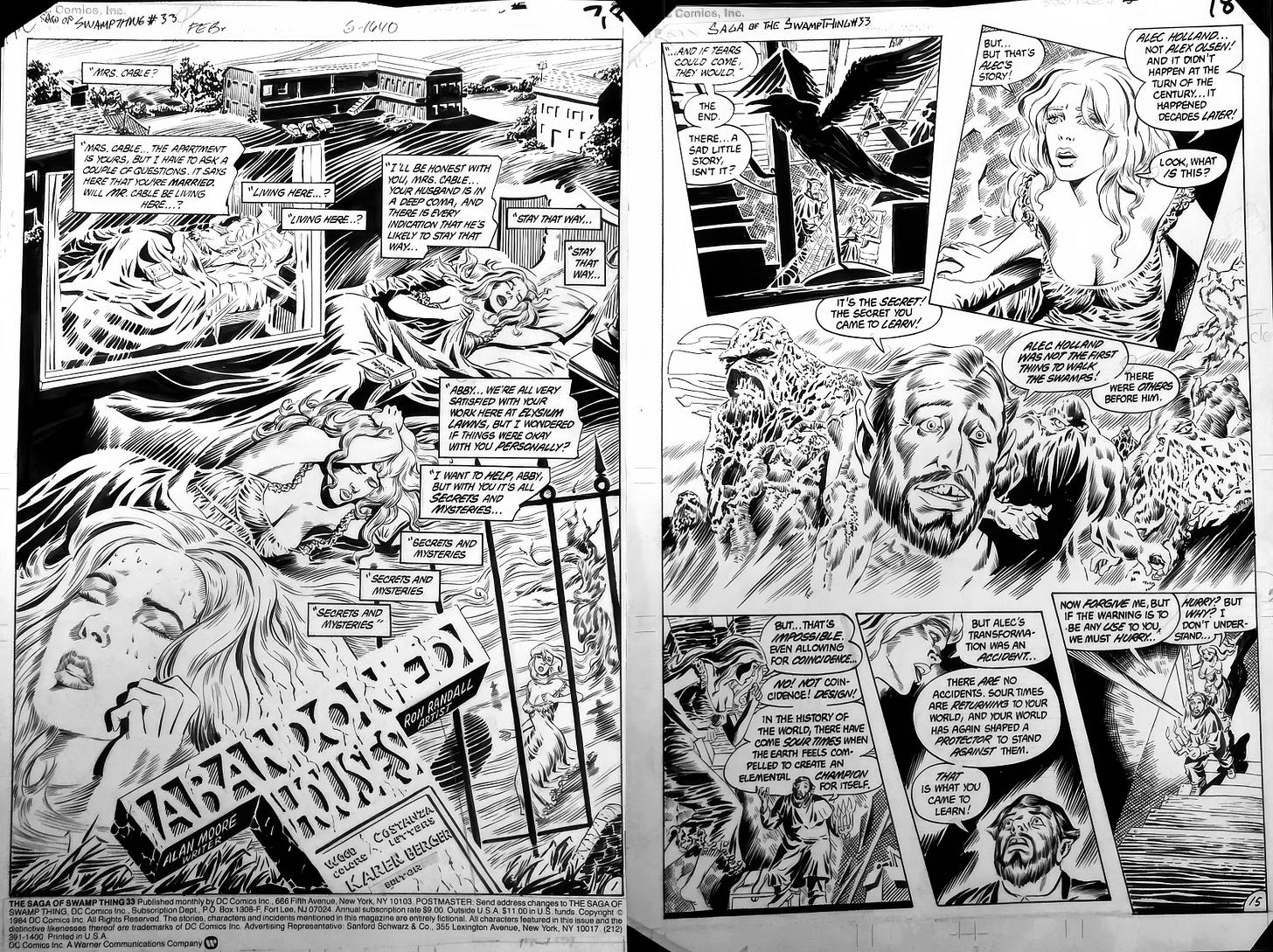

RANDALL: I was lucky enough to go to the Joe Kubert School and study with and work directly with Joe himself. So, I got a good, solid, practical education in how to go about from a master storyteller and comics legend.

BTP: Oh wow...that’s huge! I visited the school in ‘88 but never went. Were you among the first to graduate with the likes of Rick Veitch, Stephen R. Bissette, and Thomas Yeates? What was it like attending the first school solely dedicated to the craft of comic storytelling?

RANDALL: Yes, those guys were all in the first class. I came in Year Two, along with other folks like Tom Mandrake, Jan Duursema, and Kim DeMulder. In these early years the school was pretty loosely organized—they were setting it up and crafting classes as they went, I think. And most of the instructors were professional cartoonists, not trained teachers. Most didn’t have the most organized “lesson plans”, but they provided assignments, and IF you had the initiative to reach out to them and ask specific questions about it, each was a wealth of ideas and experiences to learn from.

BTP: I still kind of kick myself for not going, but my pragmatic side of “making a living as a general artist” outweighed everything. What do you feel was missing in your education vs. the reality of the job? How would you fix this?

RANDALL: The business end of it all-- how to survive financially, how to look at a contract, that stuff, wasn't addressed well at the school back then (that was long ago, the school had just opened, and by now I bet they have plenty about all of this.) How to”fix” it is, I think, happening some now, as more creative’s can reach out via social media, and talk to other artists about their experiences. That exchanging of info is powerful.

BTP: I think the lack of the business side of things, while boring as heck, was sorely missing in the early days of art schools. To your point though there is a lot more information and ways to protect ourselves today that would have prevented a lot of headaches so early on in our careers. How has technology served you in the pursuit of your comics career? Was it something you picked up easily?

RANDALL: Honestly, I picked up a lot more by being a member of Helioscope Studio, where a group of around twenty working cartoonists have shared a workspace for many years now. Everyone has their own horror stories about working with exploitative clients, advice to offer when you have a difficult email to craft… that sort of thing. But Helioscope is a rare group. For those without a group like that, I expect a lot of stories are available from creators who share experiences online. Or you can also seek out creators at conventions. Everyone has their own experiences, and some of theirs might well be ones the rest of us can learn from about how to survive this odd little profession.

BTP: That’s really great advice, Ron. As creatives we tend to have personal goals or aspirations for ourselves. What are yours and what does achieving that look like in the next 5 to 10 years?

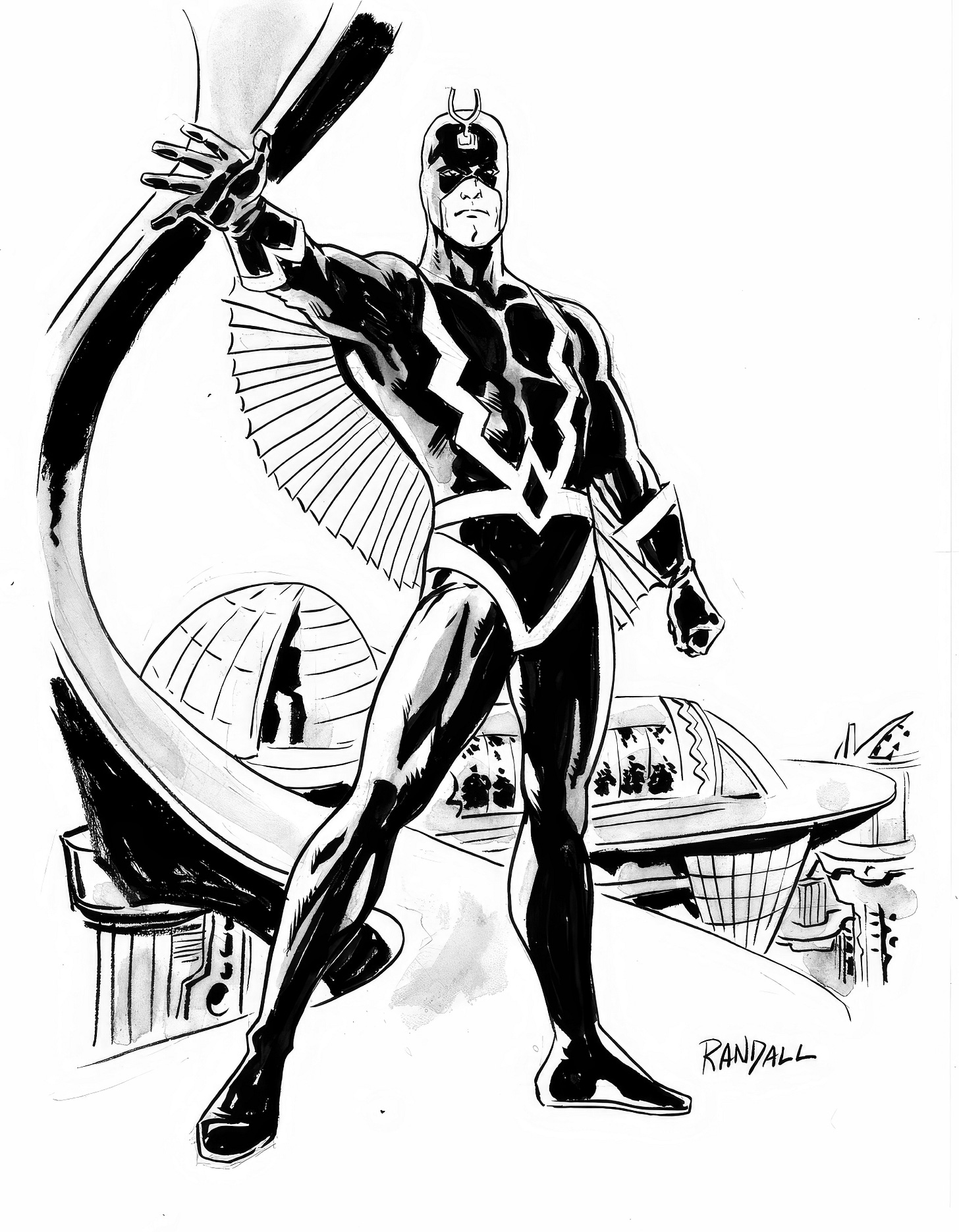

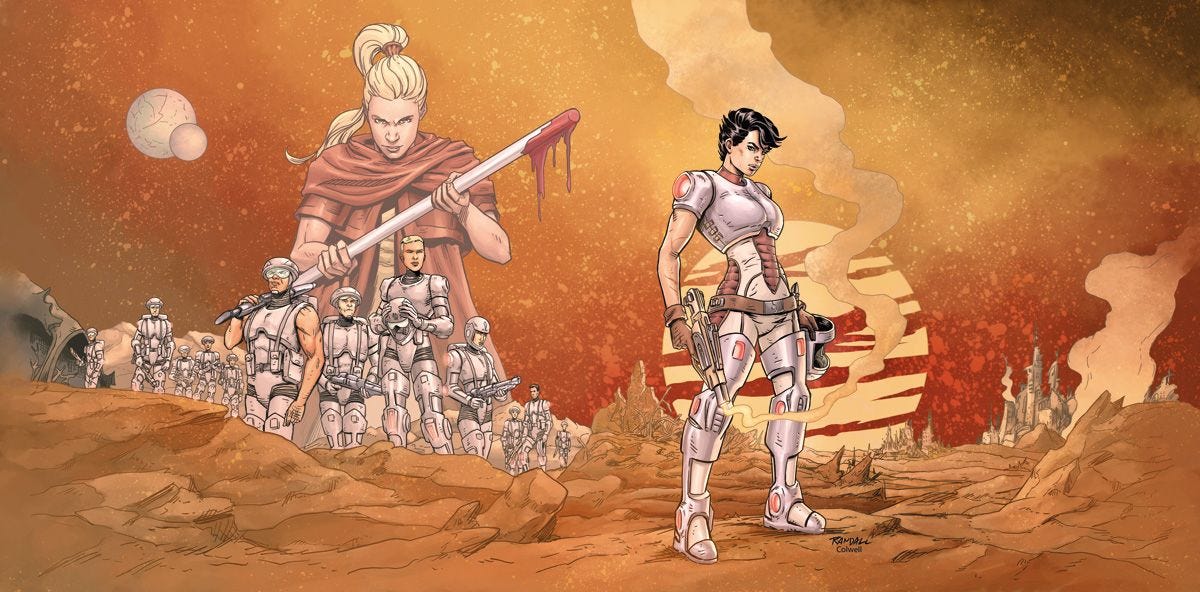

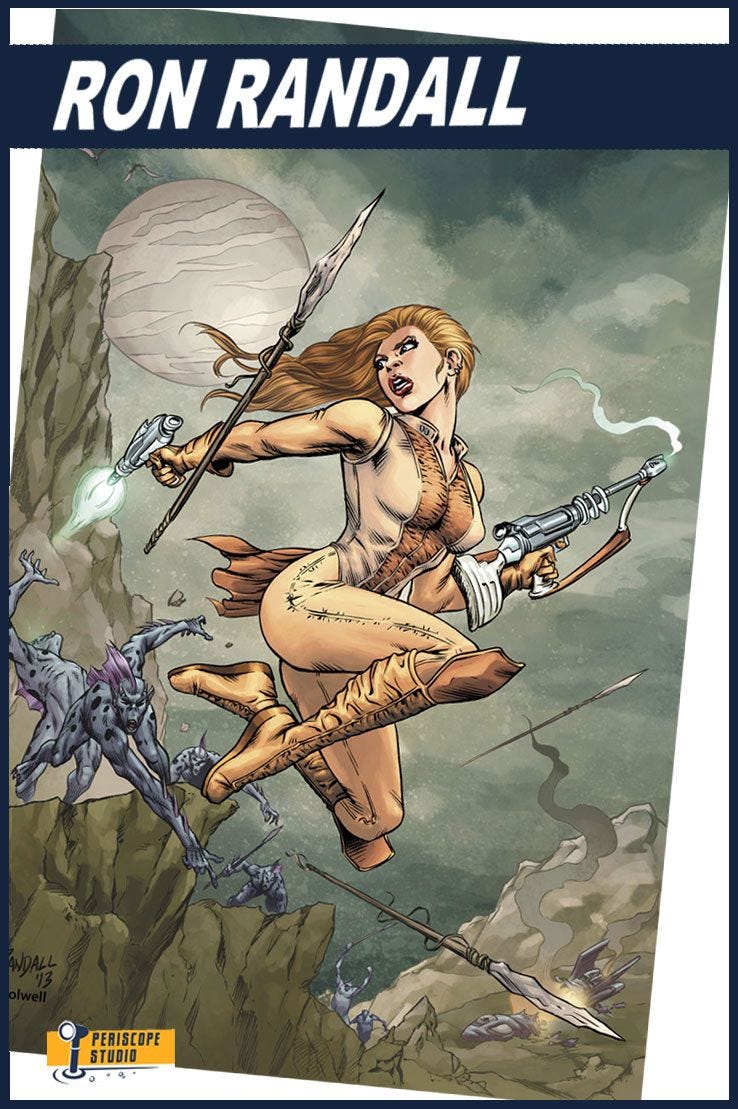

RANDALL: I'm working on my long series of graphic novels, TREKKER. The arc of her journey is nearing its long-planned resolution, and I'm excited to get there and to try to "nail the landing" for the readers.

BTP: From what I gathered, TREKKER started out in the pages of Dark Horse Presents back in the 80s. For something that has spanned so many years did you have the entire story blocked out from the beginning or did the ending manifest as you progressed from story arc to story arc?

RANDALL: More the latter. When I created the series, I always intended it to grow and expand over time, and to have it ultimately reach a resolution. But I was pretty sketchy about the details at first. But Dark Horse wanted to put the character into her own book right away. So I sort of jumped in and figured I’d start with small-scale action adventures that I felt I could tell pretty well, and drop “seeds” and references to things that I’d develop as things went along. And it’s worked out pretty well, I think.

By now, I absolutely have the rest of the series outlined, and know just how I’m going to get to that “resting point”. Each of the books is a significant step along that path. Though each is also built to be a satisfying, stand-along sci-fi action adventure as well.

BTP: What are your biggest fears in your career currently and what are you doing to keep those in check?

RANDALL: Comics is always a volatile market, and I'm using the Kickstarter to fund the TREKKER books. I'm thrilled to have a solid and loyal set of backers who have funded ten campaigns already. Still, each campaign is different-- people lose jobs, the economy takes dips-- so there's always anxiety about how well the next campaign will go. I just try to make a good comic, and then to build and run as smart and fun a campaign as I can. So far, so good.

BTP: You’ve had a lengthy run working for many different companies. The concern of editors not calling you eventually hits all of us. How have you dealt with that in your career, and did you have a solid base to bring TREKKER to the forefront at that time?

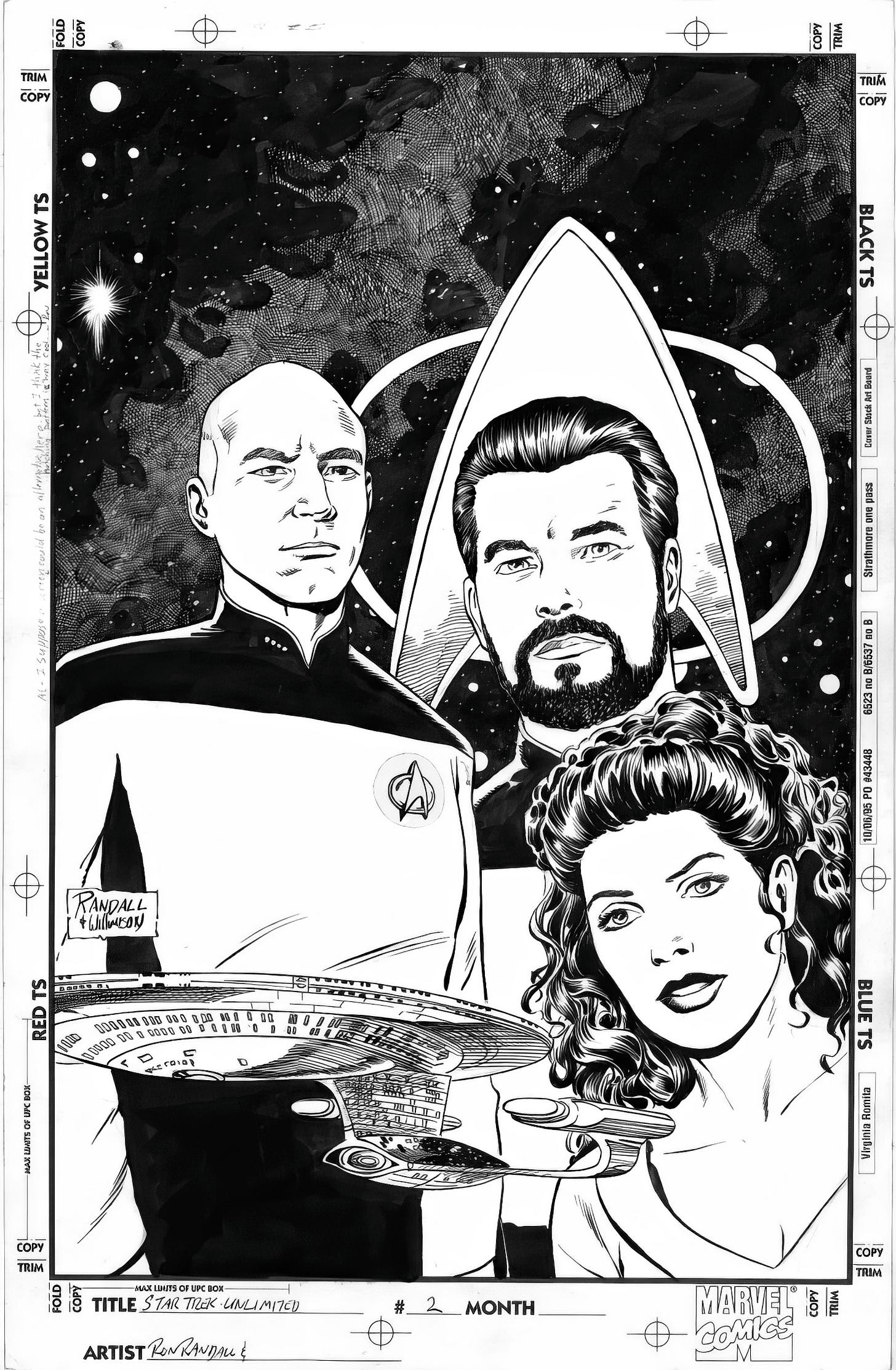

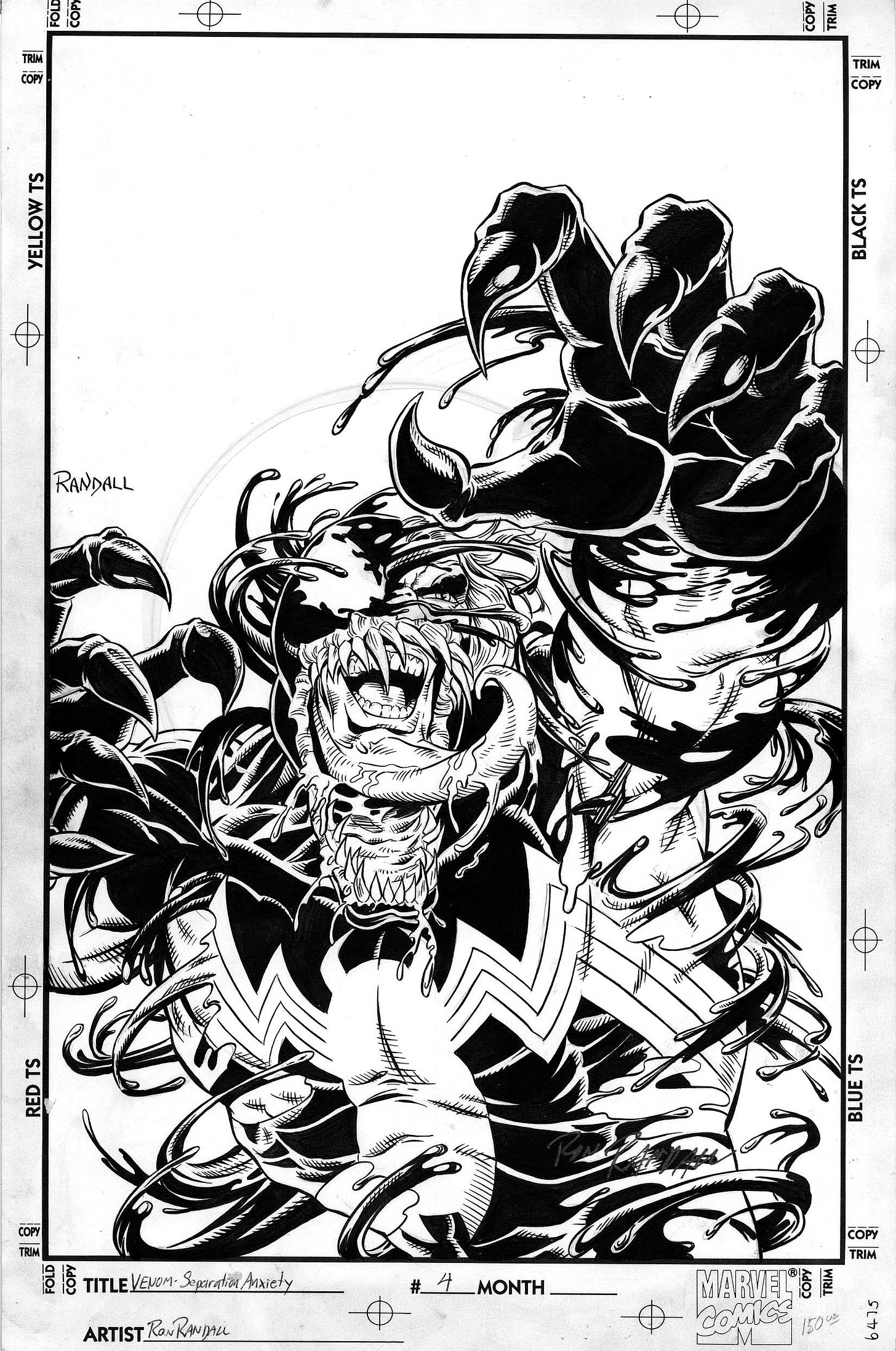

RANDALL: My answer for the “how to get the next assignment” became “be as versatile as possible”. I had a few years where I only got work as a penciller, others where I only picked up inking assignments, and others where I did both. It was a scramble at times. I tried to deliver solid work, on time, and not burn any bridges. And mostly, I’ve been able to keep work on the drawing board.

When I decided it was finally time to get back to Trekker in earnest—as pretty much a fulltime job until the story is completed, and that turning to crowdfunding would be my best chance at making this happen, I had absolutely no idea how many readers would have remembered the series, and be willing to seek it out and supporting it. So, hitting that “LAUNCH” button for the first time was a big unknown. But—I’d had a lot of help and advice from colleagues who had run successful campaigns, and I did the best I could to build a good campaign and get the word out. And happily, it funded in the first day and a half, and we were off and running. Turned out, a lot of people did remember the series fondly and were excited to see it was back.

BTP: That’s fantastic! That had to be a pretty big confidence booster. Describe the perfect day for yourself. Comparatively, what would be the perfect workday?

RANDALL: Too many options for a "perfect day". And perfection is lifeless, anyway. As to a good workday, it's being productive, riding a wave where the work flows and comes out well. You take those days when you can get them, and NEVER count on them. The rest of the time, you slog along doing your best.

BTP: I’ve never heard perfection described that way...but you know...you have a really good point, Ron. Both Lance and myself strive for perfection, but I think we also recognize if we don’t let go we’ll squeeze the life out of the work. That being said, could you please give us an idea about your working process? In a good week about how many pages of pencils and inks do you produce?

RANDALL: When I was working on, say a monthly book for DC or Marvel, I’d shoot for 1-2 pages on pencils/day, and a pretty solid 2 pages of inks/day. I mean, to make a monthly deadline, that’s what the math requires. And that’s where “perfection” becomes the deadly enemy. Occasionally, I’d draw something that felt just right, but mostly I’d hope for many 75% -80% of what I was after, then say, “better luck next panel”, and move on. Because the deadline wouldn’t wait. Kubert used to say a professional was someone whose work never fell BELOW a certain level.

With Trekker, I’ve changed my workflow a few times. Now, I write the story outline and get that polished up with my editor (yes, I pay someone to edit my work. Alissa Salah. And her insights and suggestions are golden). Then, I layout, or “thumbnail”, the entire story—usually 65-75 pages. That might take a week or so? I don’t time myself. Then I pencil the whole thing (again trying for average about 2 pages a day), then ink it all, then do letters, and finally colors.

BTP: Oh interesting. I’ve tried several methods myself. Including what you described. But what I found was that the work felt too assembly line for my taste. What I do now is break it up into 5–10-page chunks, where I bring everything to finish and then start on the next set of pages. Though the one downside is, I don’t see as many story mistakes that way. What advice would you give to your younger self regarding your life’s path thus far?

RANDALL: It’s a fair question. But given that I've ended up in a pretty good space-- getting to work on my own "passion project" on pretty much my own terms, it's hard to answer. I could always say, "spend more time studying art, do more life drawing", those are always good things. But I did the best I could, tried to take advantage of the opportunities that I lucked into, and just kept going.

BTP: And that’s a very fair answer. I think artists sometimes don’t give themselves enough latitude. Those who strive to do better, to make something out of nothing, tend to find ways to beat themselves up. Most of us do the best we can with what we have. It’s how we’ve always operated. When people who are actually producing decent samples these days come up to you at conventions and ask you for advice about “breaking in” to the comics business, what do you tell them?

RANDALL: I try to find one to three notions to point out, just next steps they might want to take with their work. That might be “vary camera angles more”, or “work on your perspective”, or the one that works for every artist: do more life drawing.

BTP: What is the most difficult thing you’ve had to do in your career and how did you make it through?

RANDALL: Some years back, I lost the job drawing the monthly Justice League International book for DC. And that was hard. I had to struggle and scrape to pick up jobs here and there for a while before things got steady again.

BTP: There was a time years ago when editors took care of their creatives, gave them fill-in issues or inventory issues to keep them paid. But with the competition of creatives from all over the world the landscape of sustainability has shrunk. While we certainly get more interesting influences in comics, the hustle to maintain any income becomes harder and harder. I think that’s why it’s so great that you’ve leveraged your fanbase and have TREKKER coming out on a regular basis.

RANDALL: Thank you—I agree that the hustle to earn even a modest living in comics is more demanding, for many creators, than ever before. I am deeply grateful that circumstances, timing, and a lot of loyal and dedicated fans have allowed me to continue TREKKER on my own terms. It feels like a rare privilege, to be honest.

BTP: I want to thank you Ron for spending time with us today. It was a great conversation. Where can people find out more about you and your work these days?

RANDALL: It’s been a pleasure!

I have a professional website, ronrandall.com for those interested in my work in general. For Trekker, you can always connect to the latest developments at Trekkerkickstarter.com, and the website Trekkercomic.com, where I post a new page every week.